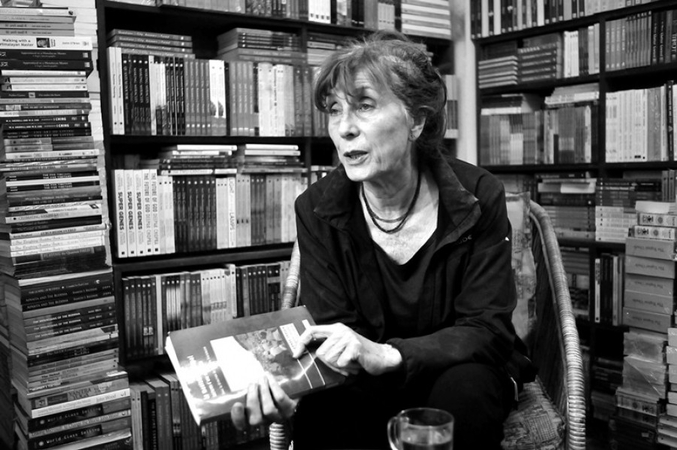

Brigitte Steinmann: ‘Studying culture helps to understand the aesthetic feeling of a society’

Anthropologist and researcher Steinmann talks about her research works in Nepal, her love for reading and her interest to study societies.

Thamel is quieter than its usual self when Brigitte Steinmann, a French anthropologist and professor, arrives in Jyatha. Steinmann was visiting Nepal Tribhuvan University’s Anthropology Colloquium Series, organised by the Central Department of Anthropology, and for the launch of her new soon-to-be-released book Exorcising Ancestors, Conquering Heaven: Himalayan Rituals in Context.

It’s clear by the name of the book that this isn’t the 69-year-old’s first visit to Nepal. Ever since her first visit in 1980, she has been visiting at least twice a year. Steinmann’s research on Nepal has highlighted the Tamang culture and lifestyle, and brought the dynamics of class divisions to the fore. Steinmann has also documented political events that brought change in the country since the 1990s. In an interview with the Post’s Srizu Bajracharya, Steinmann talks about her research in Nepal, her love for reading and her interest in studying societies. Excerpts:

What brought you to Nepal in the 1980s? Why was Nepal your first choice for your study?

I came for a scientific programme organised by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique France. This programme intended to describe the lifestyle of the Nepali people of the time, in the agricultural villages for my PhD research. CNRS was interested in understanding how people could survive with such low income. The programme put together geographers, economists, agronomists and anthropologists. My field research area was Temal, Kavrepalanchok.

Initially, I was engaged in the mixed programme. But, as an anthropologist, I started to discover that there were very different types of people living together like the Magi, Tamang, and Brahmin. And so, I was interested in finding out about the Tamangs.

When did you learn the Nepali language? Is it a language you have grown used to because of your research works?

I learnt the language in 1978, before coming; first in the French School of Oriental Studies, and second, with the Tamang people. When I came in 1980, I could speak in Nepali, but when I went to Kavrepalanchok, the place where I was conducting my research, I realised what I learnt was not the Nepali language that people used there. Most of the people were Tamang, and they spoke in the Tamang language, a Tibeto-Burman language which was an unwritten language at the time. So, it added to the difficulty to adapt.

What did you observe during your time here in the 80s?

At the time, an irrigation project had just reached the area, and it was creating conflict between caste groups. They were discussing where to put the water tank. This was during the Panchayat period, and it was interesting to understand how people were clinging to a political party, what their sense of politics was and what it meant for them. Many Tamang people were involved in trekking, and that was taking them everywhere in Nepal. But the Tamang people also had a different idea of Nepal; they called Kathmandu Yambu, which means Nepal in the Tamang language. For me, that was interesting because we were already in Nepal, and I wanted to understand what made them see things that way.

What I liked was that people shared everything, and were able to accept a foreigner with great heart and interest. Their conflicts were limited to the use of water at the village spring. For example, the Brahmins and the Tamangs would take turns to use the spring water. Life was very simple although it was very hard.

How did your interest in ethnographic research develop?

Initially, I studied philosophy, Latin, Greek, science and literature in France. And then I turned to ethnology in the 70s; it was just after the civil unrest of May ‘68. In 1968 we had a revolution that arose through questions related to the changing and transforming of times and mores. There were many demonstrations, and I was starting to get interested in ethnology. A new department had just begun in science universities. And I came to understand that ‘ethnology’ was a kind of scientific way to learn about societies.

I was initially interested in philosophy, but I always knew I was interested in learning about the ways of living in society, moreover different societies to mine. I also loved travelling and knew about Nepal from before because of its ties with Tibet. I heard about Tibet from my grandfather because he was friends with Alexandra David-Néel, one of the first women who were able to enter the city of Lhasa in 1905. I was also interested in Nepal because of mountaineering, something I did in the Alps and later in Lhotse and Kanchenjunga in the 80s.

Why study Asian cultures, specifically?

In philosophy, we study philosophical systems, ideas, history of concepts. Initially, anthropology was for me a part of the philosophical system of Kant (a german philosopher). But I wanted to experience non-western societies. My first choice was Amazonia, Brazil; I was v attracted by the population living in the forest. I didn’t imagine that I could do some ethnology in Nepal. Because in France, ethnology and anthropology studies were developed in Africa, as there were French colonies in Africa, I was not attracted to French post-colonial societies.

At the time, I would have preferred to go to Tibet, but it was not possible because Tibet was still locked down. Fortunately, I heard about CNRS’s programme in Nepal and joined.

What is your role as an anthropologist?

The role of an anthropologist is to be with people. Through anthropology, you can study social organisation, kinship systems, religion. Above all, you learn about the real meaning of ‘being a stranger’ in the world.

Here in Nepal, I started to try to describe the economic system of the time, despite the term’s irrelevance to the mode of production of resources by the people. They were producing everything from the start to finish, and money was of no use; everything was hand made. Everything was transparent and we could understand their infrastructure easily; houses were made with earth and wood; complex rituals presided over the construction.

As an anthropologist, I tried to document how they were organising their world or how they explained the ways they were creating their world. I was also very interested in learning about their religion, and I began to understand locally the differences they made between Hinduism and Buddhism. The Magars were mainly Hindus and Tamangs Buddhists. But society was complex, especially the Tamangs: they had Tibetan script, but they spoke in Tamang language, and I wanted to find out about the interconnection between them.

As an anthropologist, I wanted to study the communities in Tibet too. In 1981, I travelled to the north-eastern border of Kanchenjunga area with someone from the village where I was staying. We reached Walungchung Gola, an isolated big Tibetan-style village with a huge Gompa. That was my first experience living with a Tibetan society. So, I did one of my studies here.

Why do you think cultural studies are necessary?

I won’t speak in terms of culture, as it is a kind of ‘void’, or too global notion. Culture is everywhere. But, intrinsically, studying the particular culture of a society helps to understand what I would term as ‘the aesthetic feeling’ of being part of an organisation. It also gives a ‘philosophical sense’ to the notion of society. And so, I have seen and experienced different modes of people’s lives.

The 80s also gave me the happiest feelings of my life, just being there with the community gave me a lot of opportunities to learn. There was a lot of complexity at the time as people didn’t accept me so easily as I was an outsider. They always wanted to give me a place among them. There was much to observe.